How TAE's fusion reactor will work (or won't)

The TMTG and TAE merger has made fusion energy a headline news topic again. It is causing non-experts and investors to ask a basic question: "What, exactly, is TAE building and how close is it to working?"

This piece is the first in a series where I’ll explain the fusion reactor concepts being pursued by fusion companies and then evaluate company claims using the standard metrics of fusion physicists: plasma temperature, density, and confinement (plus the realities of power balance and economics).

For this article, I’ll start with the story of how "alternative" fusion ideas like TAE’s survived when government funding narrowed to a few mainstream paths. Then I’ll lay out TAE’s argument for its field reversed configuration (FRC) approach and “clean” p+B11 fuel. Finally, I’ll show why many fusion experts remain skeptical by using published data to demonstrate the scale of the performance gap and what would have to be true for “first power in 2031” to happen. My goal is to give a clear and sober picture of where TAE is and what they need to do to get to where they say they are going.

Background

Before diving into TAE's fusion reactor concept and the wider fusion community's critiques, it is important to set the stage with the history of how fusion funding and R&D evolved and how TAE became what it is today.

Mainline and alternatives

The 1950s through the 1970s saw a rapid expansion of concepts on how to build a fusion power plant and many experiments testing them. This research was almost entirely funded by governments. The 1980s through the 2010s were years of contraction and focus. This was due in large part to the growing expense of experiments as they approached power plant scale and the reducing appetite of government funding for a futuristic energy source with uncertain timelines. Naturally, the government focused on the "mainline" concepts leading in performance: primarily tokamaks, stellarators, and laser inertial systems (although laser inertial had extra support from nuclear weapons stockpile stewardship programs). This left the other "alternative" concepts either with reduced funding or completely abandoned.

A number of the scientists who believed in the potential of their alternative fusion reactor concepts found refuge in private investors. The basic story told by these proponents to investors is that the government-funded fusion projects are too big and complicated to make economically viable fusion power plants. Their alternative concepts had great potential due to a simpler machine design. They were unfairly pushed aside before they were able to demonstrate better physics performance and improve Q – the fusion power gain – to what is needed for a power plant. Many incorporated narratives of using fuels "cleaner" than the deuterium-tritium that was proposed by mainline fusion efforts.

The late 1990s through the late 2010s were a challenging time to raise money for private fusion, as it had not yet become a widely acceptable investment class to the venture capital community. Proponents of alternative fusion reactors found that they were able to sell their stories of a faster path to fusion energy to high-net-worth individuals. These investors got excited about the clean energy potential of fusion and the prospect of getting in on the ground floor of what may be a world-changing industry. Of note, two of the longest-lasting alternative reactor concepts that have raised well over $100M are TAE Technologies founded in 1998 (then called Tri Alpha Energy) and General Fusion founded in 2002.

Dogmatic convictions

This brings us to today. The fusion energy industry is at a fascinating point in its development: Decades of research have produced an enormous variety of concepts, see the figure below, as well as impressive improvements in our understanding of fusion physics and engineering. Essentially all of the high-level challenges to fusion energy are well laid out and many of these challenges have detailed plans on how to be addressed. Yet, we (I will use "we" in this article in reference to "the fusion experts") are far from a consensus on what form an economically viable fusion power plant will ultimately take.

In my opinion, this is due to the immense challenge of fusion energy: It is a complicated, interdisciplinary technology with very complex physics at its heart. In addition, it has a very wide space of configuration possibility. Combine this with the variability of what problems individuals think (or believe) are harder/easier and more/less important to solve along with finite funding, and the result is what may look like religious beliefs in which concept is the path to fusion energy.

Framing the discussion

To fusion outsiders – and some insiders – it's hard to differentiate among the different concepts and separate out fact from opinion in the narratives that are told around them. For any given concept: there are proponents who will argue to the grave that theirs is the only way to a fusion power plant, there are opponents who will argue with absolute conviction that it has no chance of working, and there are many people occupying the middle.

In discussing contentious issues like the tradeoffs of different fusion reactor concepts, I lean on Rapoport’s Rules for a productive framing:

- Explain the other person’s position clearly, vividly, and justly.

- Mention anything you’ve learned.

- List the points on which you agree.

- Only now make a critique or refutation.

Due to the efforts of many brilliant fusion physicists, we understand much of the physics to point to where the challenges of different concepts can be laid out quantitatively. We know the targets in temperature, density, and confinement time that a fusion reactor must achieve to have even a hope of being a power plant, and we can measure what they are in experiments. We can calculate and estimate how power flows and where it is lost. Thus, we can have productive discussions on how concepts fare as potential fusion power plants.

With that as the backdrop, I'll now frame the fusion industry's discussions on how TAE's fusion reactor will work (or won't) using Rapoport's Rules.

TAE's public position

Fortunately for this discussion, TAE has published peer-reviewed articles on their experiments and their results as well as put out public information on their vision for how that translates to a fusion power plant. I, having managed intellectual property at a private fusion company, suspect there are important details they are not sharing publicly to try to maintain a business advantage in the industry. In addition, the narrative they have told to their private investors likely has more details than what is public. So, the complete picture is not publicly available. We will see whether and how information access changes with the transition to being a public company under the TMTG merger.

TAE's differentiation centers on their choice of fusion reactor concept as well as the fuel they propose to use.

Claimed FRC advantages

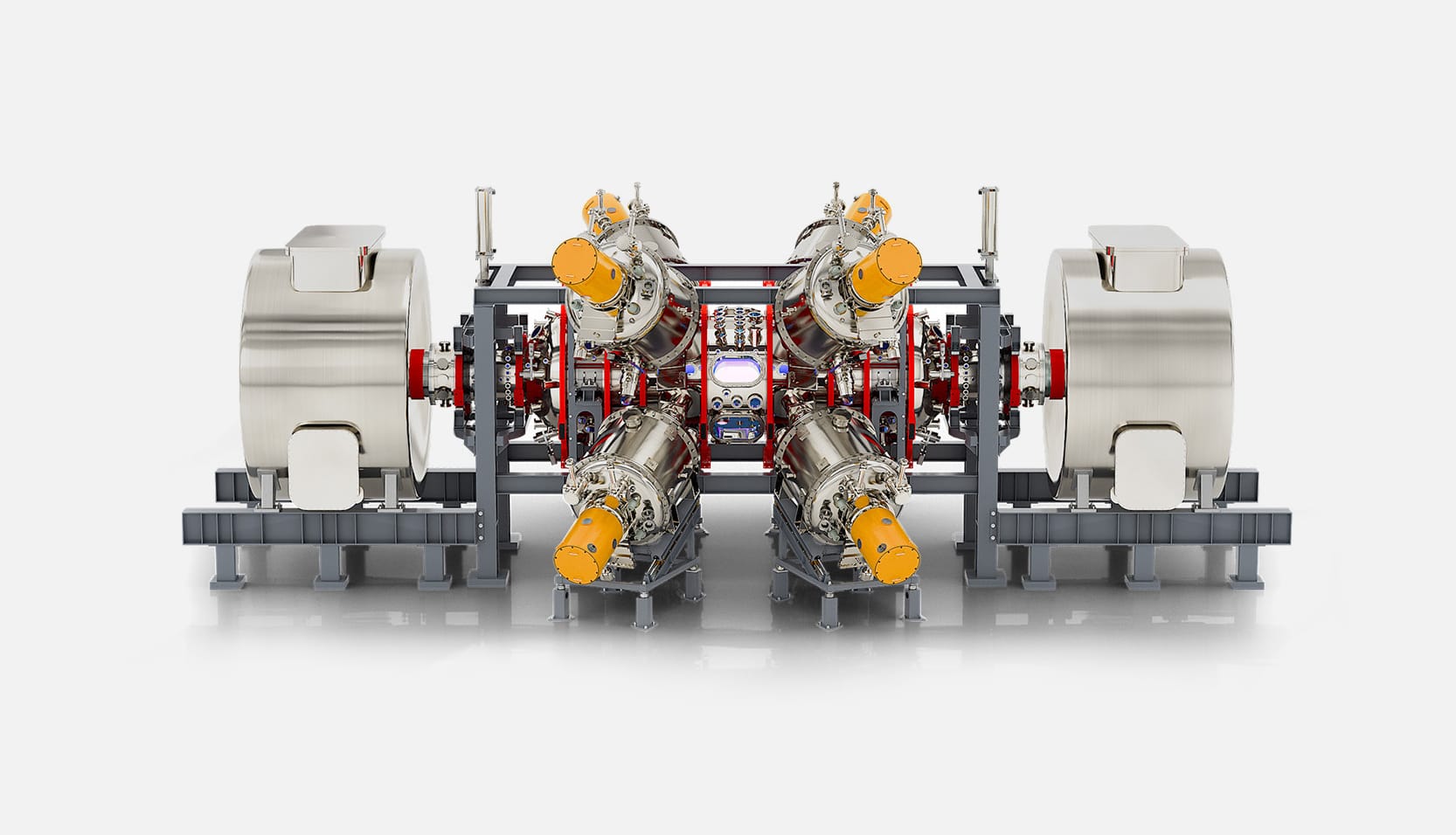

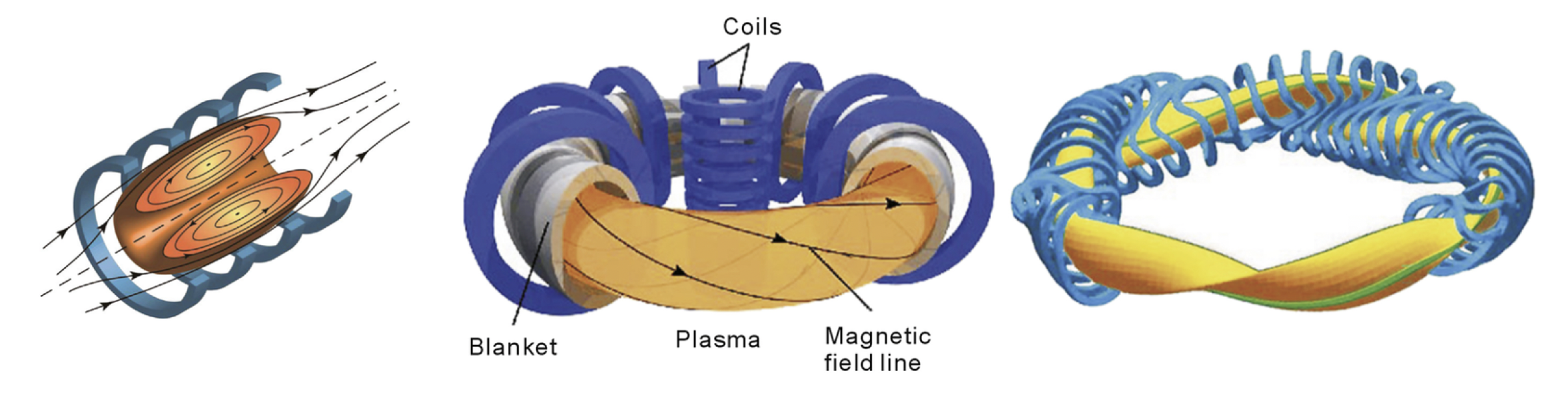

TAE is using a magnetic confinement concept called a field-reversed configuration (FRC). The FRC is named as such because the magnetic field from the fusion plasma is reversed in direction from an externally applied magnetic field. It is part of the magnetic confinement class of fusion reactor concepts where a magnetic field is used to try to insulate and maintain a plasma at fusion-relevant conditions.

In contrast primarily to the two leading magnetic confinement fusion concepts – tokamaks and stellarators – FRCs have the purported benefits:

- High‑β: In magnetic fusion, β ("beta") is the ratio of the plasma pressure to the magnetic field pressure and acts as an efficiency figure of merit. For a given fusion power output, which relates directly to plasma pressure, higher β means lower strength electromagnets, which are less expensive and easier to create. The physics of each fusion concept fundamentally limits the β it can achieve. Stellarators have demonstrated volume-averaged β ~5%, spherical tokamaks ~15%, and TAE's FRC >90%.

- Compact: The plasma in a FRC is self-contained and has no interlinkage with external structures as is the case with the central legs of the magnets for tokamaks and stellarators. This lack of interlinkage can make for a more efficient use of space and reduce the challenges of design, construction, and maintenance.

- Axisymmetric: FRCs have very simple cylindrical axisymmetry, which makes design, construction, and maintenance much easier.

- Simple external coils: The electromagnetic coils are all simple rings, external to the other systems, and easily assembled and disassembled for maintenance.

- Linear power exhaust: The linear geometry of the machine allows for plasma power exhaust out of the ends, which enables expansion and reduction of power densities to tolerable levels. Tokamaks and stellarators are closed and very limited on expanding power exhaust; they must reduce power exhaust by other more challenging means.

Claimed fuel advantages

There are four main fuel pairs considered for fusion energy production. Deuterium-tritium ("D+T") is considered by many the most likely fuel for first generation fusion power plants due to its having the lowest requirements on plasma confinement. The two main disadvantages for D+T are that it requires the tritium to be produced within the fusion plant, and that it produces high energy neutrons as a direct result of the fusion reaction. Both of these are major challenges for fielding an economic D+T fusion power plant.

TAE has long planned on using proton-boron-11 ("p+B11") for its fusion fuels. p+B11 is considered by many to be an "advanced" fusion fuel because it must reach much more challenging plasma conditions (hotter, denser) than D+T. The main advantages for p+B11 are:

- Abundance: Both fuel components, protons and boron-11, are highly abundant on Earth and don't need complicated tritium breeding, extraction, and purification systems.

- Fewer neutrons: Neutrons are not a direct part of the primary fusion reaction, but they are produced to a much smaller degree (~0.1%-1%) in secondary reactions. Consequently, there is a much lower neutron flux on the surrounding machine and therefore much less damage and longer component lifetimes as well as less activated material.

Some in the fusion field, including TAE, consider the D+T challenges insurmountable or not worth the effort given the potential advantages of other fuels. Rather than solving the "engineering" challenges of D+T, they consider the "physics" challenges of getting better plasma confinement needed for p+B11 to be the better path to pursue.

Learnings from TAE

Much can be learned from TAE and what they've accomplished:

- Private-sector fusion is a viable path: TAE is a pioneer of private fusion companies. They have demonstrated that raising significant capital (>$1B) is possible for private fusion and have used it to make real advances on their fusion concept.

- The mainline is not the only path to walk: The focus of public-sector fusion funding on a small number of fusion concepts was not healthy for a vibrant fusion ecosystem. For our best shot at fielding fusion energy, we need a variety of concepts pursued.

- Old dogs can learn new tricks: While FRCs were set aside for some good reasons (e.g., poor stability), TAE has demonstrated that dedicated research can solve old problems. They've made good advances in stabilizing and improving FRC performance over decades of research. Also, TAE has found ways of simplifying the FRC system: they no longer need to collide two plasmas to form their FRC; instead, they have figured out how to use their external neutral beam heating systems to initiate and maintain the FRC plasma.

- Updated nuclear data can change outlooks: New research into p+B11 reactions has improved the outlook for the viability of using it as a fusion fuel.

Agree with TAE

TAE is right about important issues:

- Tokamaks and stellarators are hard: They require complicated, high-field superconducting magnets. Their interlocking components make maintenance hard and challenge the ultimate economics. While we should work on these concepts, we should also work on others in the case that neither tokamaks nor stellarators turn out to be an economic fusion power plant.

- Advanced fuels have desirable features: Tritium breeding and D+T neutron damage are hard problems that would be great to avoid. p+B11 is very challenging, but would afford benefits if it could be made to work.

- "Hot Enough" and "Long Enough" framing is correct: Confinement time and temperature – along with density – gate fusion gain. TAE uses this framing to gauge their fusion progress.

- Shared commitment to fusion innovation: Many of the big government programs had been averse up until recent years to fund innovation, both for established concepts like tokamaks and for alternative concepts. Innovation is absolutely needed to get to commercial fusion energy and TAE has demonstrated that it is possible to innovate outside of government funding.

TAE critiques

Now that I've set the stage, restating TAE's position, what I've learned from them, and what I agree with them, I will dig into detail the broader fusion community's critiques of TAE's concept and plans.

Early critiques

TAE's FRC-based fusion reactor concept was revealed in a 1997 Science article for the public and a companion article for the scientific community. It received a generally negative reception from the fusion community:

- “Eight mutually consistent miracles is a lot to ask for, even in the fusion business!” – M. Lampe and W. Manheimer, Senior Scientists, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

- “...only by heroic energy conversion techniques...” – R.J. Goldston, former Director, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

- “Thus, the fusion gain [Q] … 0.02 would be much lower than the value of 2.7 stated by [TAE founders].” – W.M. Nevins, Senior Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- “...the proposal for a reactor with net electrical power output is unrealistic...” – A. Carlson, former Scientist, Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics Garching, Germany

The concerns centered around two main issues:

- p+B11 is nearly impossible to get to energy gain

- The TAE FRC concept relies on “heroic” efforts to keep particles out of thermodynamic equilibrium

While TAE's design has evolved and improved since 1997, most of these concerns remain substantially unresolved.

The hardest fuel

p+B11 has the hardest requirements on any of the fuel pairs that are considered as candidates for fusion energy generation. It needs the highest energy confinement time as well as the highest plasma density and temperature (a comparison to D+T and TAE's performance is shown later). No fusion reactor has come remotely close to the conditions needed to use p+B11. In fact, only laser inertial fusion and tokamak magnetic fusion are in the right ballpark for even the easiest fuel pair, D+T.

In addition to having harder conditions to reach, p+B11 fusion conditions are harder to maintain. A p+B11 reactor is likely to cool faster than the fusion power or external heating can keep up with. Much like how things like steel glow as they get hotter, so does a fusion plasma. The electrons emit light through a process called "bremsstrahlung" and the power in the light is lost from the fusion plasma, cooling it. This is made worse by the presence of boron nuclei with a high charge (+5). At the temperatures needed for p+B11, the plasma glows so hot that it emits hard x-rays.

Fighting entropy

TAE's public plan to improve the chances for p+B11 involves keeping the proton ions, boron ions, and electrons that make up their fusion plasma at different temperatures and away from thermodynamic equilibrium.

The basic idea is to keep the electrons colder than the ions, which reduces the power loss caused by bremsstrahlung radiation. TAE is trying to force the ions to have a higher fraction at the ideal energy for fusion by means of injecting protons using a high energy neutral beam, which requires a lot of power to do so.

This is all fighting against the second law of thermodynamics, which dictates that heat flows from hot to cold (thereby increasing entropy). Lampe's and Manheimer's "eight mutually consistent miracles" summarizes the different ways in which the second law of thermodynamics is spoiling TAE's plans. One can think of the problem in part due to "friction" among the proton, boron, and electrons causing them to exchange energy.

High recirculating power

A further criticism of TAE's plans involves the need to "recirculate" a large amount of power through the plant to maintain the plasma in the desired state. Goldston called it “heroic energy conversion techniques”. This involves capture of the fusion power, bremsstrahlung radiation, and other energy losses, efficient conversion to electricity, efficient conversion to the high energy neutral beam, and then efficient coupling of energy to the right parts of the plasma. The signs of TAE working on this can be seen in their spin-out technologies of efficient power conversion equipment and particle accelerators for cancer treatement.

However, even if they were able to get all of the physics and engineering challenges solved, high recirculating power could be a killer to plant economics. Today's economically viable thermal power plants (e.g., coal, natural gas, and fission) have ~2%-8% recirculating power fractions. TAE's concept power plant has ~40%. TAE's proposed large recirculating power systems will increase both the capital as well as operating expenses of the plant, hurting the bottom line and economic competitiveness.

Enormous performance gap

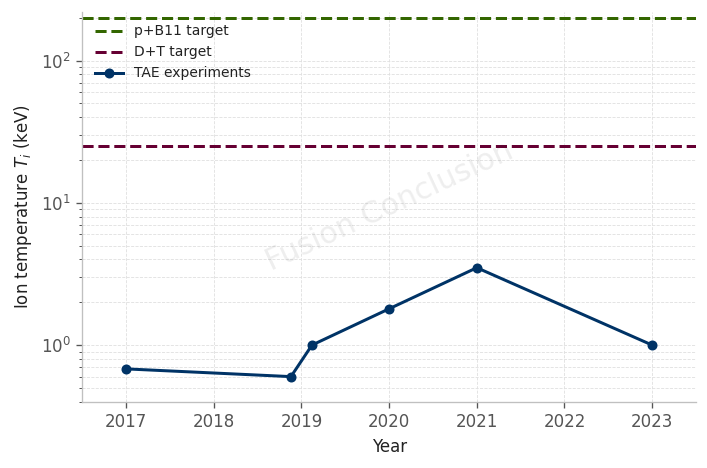

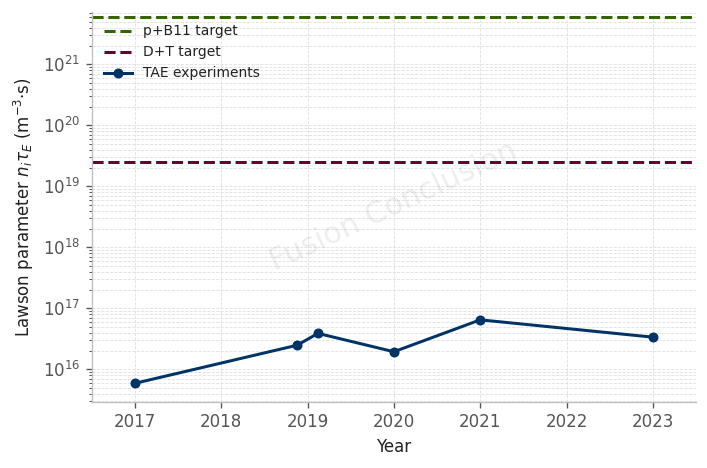

The plasma conditions needed to get to fusion energy gain have been known for decades as laid out by Lawson: for a given fusion fuel, we know the plasma temperature, density, and energy confinement time (think of this as insulation effectiveness) required. Wurzel and Hsu have benchmarked (and updated) performance of fusion concepts against these metrics.

Taking the published experimental data from TAE in the Wurzel and Hsu papers and comparing it to the ion temperature needed for D+T and p+B11 fusion we find the following:

While TAE has made progress increasing their ion temperature up to 3.5 keV (perhaps up to ~6 keV in non-peer-reviewed report), they still have a further >7x to get to D+T net-energy fusion conditions and ~60x to get to p+B11 conditions. These are enormous bounds in performance to achieve. Experience has shown that every known fusion reactor becomes more challenging to confine as temperature rises. This is because as thermal velocities increase new instabilities kick in and hurt confinement. Given their own history in performance improvements, as well as the experiences from other fusion reactors, it will take multiple generations of machines to get to p+B11 confinement conditions, if it is even possible.

Even greater improvements are needed in the Lawson parameter: the plasma density times the energy confinement time. Present experiments need to scale ~400x to get to D+T net energy conditions and ~90,000x to get to p+B11 conditions. TAE is aware they need to reach this level. This is not some small hill to climb; it is an enormous cliff to scale.

Much of the fusion community's skepticism towards TAE's timelines is rooted directly in the data that makes up these graphs. While the data demonstrate performance improvements by TAE, they also show how far TAE needs to go. And, given that difference, it is hard to believe any near-term claims for a working fusion power plant. TAE had originally planned to build a next-step reactor, Copernicus, with the goal of exceeding conditions to get to D+T fusion (while not using D+T fuel). They are now planning on going straight to Da Vinci to produce electricity with p+B11.

Simply put: if TAE somehow does make the leap from their present experiment to a p+B11 electricity-producing machine by 2031 as they have stated in their public announcements, it will be the single biggest improvement in the history of fusion by a wide margin. One may even call it a miracle.

Conclusions

In some ways, TAE has been an incredible fusion company: It is one of the oldest fusion companies still around. It has raised over $1B, much of it before fusion was a "hot" area to invest in. It has made progress, improving a very challenging fusion reactor design. And very recently, it is the first fusion company to go public.

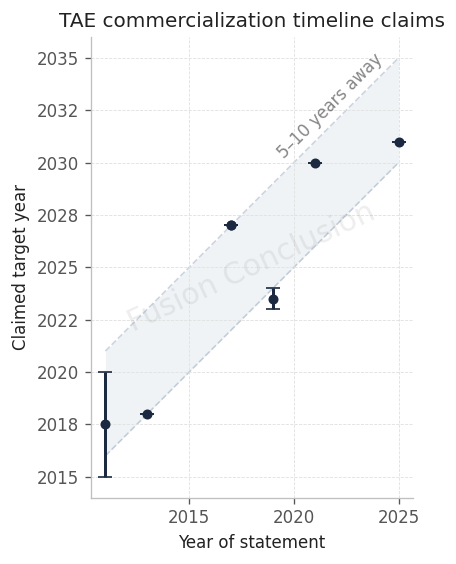

In other ways, TAE is a very curious fusion company: It has promised that its fusion power plant is just over the horizon for over 25 years. Many of the experts in the fusion field think that what TAE is trying to do is improbable if not impossible and have physics-informed calculations to back up their opinions. Despite the progress TAE has made, it is barely closer to the plasma conditions that it needs to achieve than it was two decades ago.

Given all that, it is hard to believe the company's claims that it will achieve "first power in 2031" from fusion energy. If they do, it will be a wonderful thing for clean energy generation and American "energy dominance". But I would not suggest you hold your breath for it.

About the author

Dan Brunner has a PhD in Applied Plasma Physics from MIT. He is one of the co-founders and former Chief Technology Officer of Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), "the world's largest and leading commercial fusion energy company." He built and led the team of scientists and engineers that did the conceptual design of SPARC, the D+T tokamak being built by CFS to demonstrate net fusion energy before 2030. He is now advising fusion investors and startups through Future Tech Partners.